I first visited Allan Yeomans in 2016, when I was just beginning work on the sugarcane project in Mackay. Driving north from Wollongong with Lizzie and Albie, we stopped at the Gold Coast and pulled in to the carpark of the Yeomans Plow Company. Very quickly Allan drew me into an engrossing technical and ideological conversation about global warming, government policy, and the great tradition of Aussie inventiveness that his family is so famous for.

He talked me through the prototype of his Yeomans Carbon Still – which I had read about online, but never seen in the flesh. Eventually Lizzie had to drag me away as the afternoon was getting on and we needed to find a campsite for the night. But in that couple of hours with Allan, the idea for this project was born. In a nutshell: take a working model of the Carbon Still and install it in the museum as a public demonstration of how farmers can measure their soil carbon.

Over the last couple of years, Allan and I have had regular phone chats, with updates about how the Still is progressing. I can’t say I understand it comprehensively yet. The whole thing is just too complex. For a start, there’s the whole soil science side of things – and the way that soil organic matter (the carbon) “burns off” when you heat the soil beyond 500 degrees. I mean, I get it, in a second-hand sort of a way, but I don’t really get it.

It’s like, say, taking a carpentry book out of the library and looking at the instructions about how to make a dovetail joint. It’s not until you get a saw and a piece of wood and actually try it for yourself that you properly understand the material reality of joining two pieces together. The resistance of the grain; how you need to hold the saw just so; the fact that different sorts of wood behave differently.

That’s sort of how I feel about soil. It’s the most simple, basic material (y’know, it’s just dirt, innit?) and yet its ways are so mysterious.

A few months back I asked Allan if he would come up to Mackay and run a workshop to demonstrate the Still and tell the local farmers’ groups how they could use it to track soil carbon sequestration. He said he was too busy to make the trip, but as an alternative, how about I come to him and he’d train me up in using the machine myself?

So that’s what this visit to the Gold Coast was all about – me starting to acquire that embodied material knowledge of the machine and its relationship to soil. I figured it was about time.

I invited Morgan and Sam – two young filmmakers from Wollongong – to shoot some footage of Allan teaching me how to use the Still. The idea is that the video, once it’s edited together, should give viewers a quick overview of the machine, how it works, and why we need it. And it would also tell part of the story of the intergenerational transmission of knowledge from Allan (86 years old) to me (43). Wow, I just realised Allan is exactly double my age.

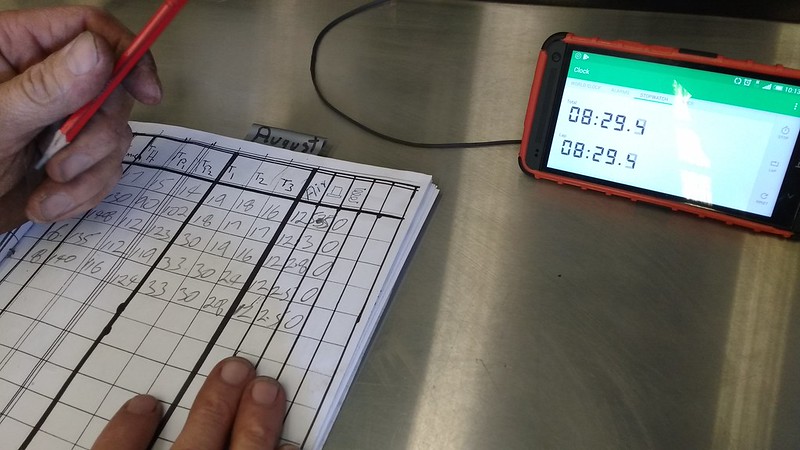

We arrived about half past three on Tuesday afternoon, and Allan jumped straight into it. He introduced us to his trusty assistant Darren, who had been “cooking” a sample of soil that afternoon (“here’s one we prepared earlier”). Morgan and Sam got some shots of the removal of the soil sample from the machine, the twiddling of mysterious knobs, and the jotting-down of an array of confounding numbers in a home-made spreadsheet.

I began to get nervous. I asked Allan what he thought my chances were of actually learning how to use the Yeomans Carbon Still independently. He sized me up with a half smile and said, “Oh, I don’t know, maybe … ten percent?”.

Ten percent!? I know I’m not among the most technically competent members of the community, but this could be a problem! I figure that if this machine is really going to take off, it will need to be easier to operate than that. And so as I worked with Allan and Darren over the next few days, I had the beginnings of a few ideas about how Allan could simplify the operations of the still.

First, he needs an instruction manual. At the moment, the only people who can “drive” it are Allan and Darren. It’s a knowledge that they’ve built up over several years during the phase of the machine’s development. But to pass that knowledge on to others, you need to have some empathy for people who (initially) have no idea what they’re doing. They’ll need step-by-step directions and a complete idiot’sguide for how to go through the whole process.

Second, some of the controls will need to be automated. During the “cooking phase”, the person driving the machine has to sit, very attentively, adjusting the knobs that tweak the rate of airflow and the heating unit, noting down every two minutes (manually, with a pencil) a set of six different thermometer readings.

Luckily, Darren is very focused, and while sitting in the driver’s seat he tended not to get too distracted by my constant questioning. But I can imagine a situation where, say, an important phone call comes through, and the operator’s mind drifts away momentarily from the task at hand, at which point the temperature spikes and ruins the validity of the soil test.

As I said before, I’m not very techy, so I don’t know how feasible this is, but surely a thermostat could be programmed to interact with the airflow and heating unit. And couldn’t the data that the machine produces be automagically logged by a linked-up laptop?

Perhaps when we put the Still on show in the museum, someone smarter than me will be inspired to create these plug-ins?